A Search Engine for Academic Computer Vision Papers

Contents

1. Introduction

With the development of artificial intelligence, thousands of papers are published every year. How to manage all these papers becomes a challenge. Besides, to better utilize these precious research results, how can we build a search engine that can help us find related work quickly and precisely?

One big success is the well-known ArXiv, which is a free distribution service and an open-access archive for 1,968,218 scholarly articles in the fields of physics, computer science, statistics, electrical engineering and so on. Undoubtedly, it is a great thing that people can find most of the papers they want on such a paper search engine, but it can be improved in many aspects. First, ArXiv is sensitive to typo. Even if you capitalize or forget to capitalize a certain letter, you might fail to find desired results.

Second, the searching algorithm in ArXiv is not intelligent enough to understand your query. For instance, if you have just started your journey in computer vision and want to know more about the famous “ResNet”, you cannot find the paper if you search for “Residual networks”. Instead, the title for that paper is “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition”.

Third, during paper review, researchers need to search for a specific topic or method. For experienced researchers, these might not be problems, but beginners need a more friendly platform.

Based on the reasons above, we aim to design a search engine for searching academic papers.

- It should be friendly to users who are not very experienced in computer vision, such as students.

- Users can search for specific topic or method, such as ‘Transformer’, ‘Bert’, ‘MLP-Mixer’, and obtain relevant papers which use these methods.

- It is robust to small typo problems. For instance, if a user types “RexNet”, the search engine will still find papers related to “ResNet”.

We built the search engine through a learn-to-rank model trained by lightGBM (also LGBM), which is a powerful machine learning model frequently used for classification and ranking. Our model takes multiple features as input and outputs a list of papers with high relevance scores.

2. Data

Before comming to the step of model building, we have to obtain a well-labeled dataset for this specific task.

We choose papers that are published on Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) and International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) as our data. CVPR is an annual conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, which is regarded as one of the most important conferences in its field. ICCV is another top conference in computer vision and is held every two years. We choose CVPR and ICCV as our domain because many outstanding papers are published on them.

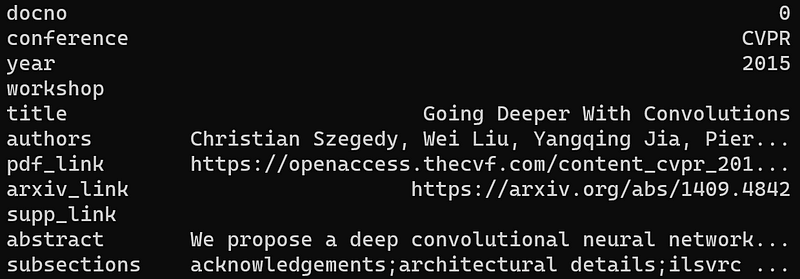

Selenium is a convenient autonomous crawler in Python. With Selenium, we obtained approximately 15,000 papers published in CVPR and ICCV from 2015 to 2021. Each paper can be treated as a document, which consists of title, authors, abstract, LaTex version, publised year, whether it is in the workshop and whether it has supplementary material. And we use regular expressions to extract the subsections from the latex. The obtained data are stored in Pandas DataFrame.

An example of our crawled papers

The next step is to select several queries and annotate the relevance between the queries and some candidate documents. The candidates are first retrieved by classical methods like BM25. We scored the relevance from 5 (very high relevance) to 1 (very low relevance) and separated the dataset into training data (40 queries), validation data (10 queries) and test data (10 queries).

3. Methods

Initially, we use PyTerrier to index the documents and retrieve 50 papers with top relevance. And then learn-to-rank model will be applied to reranking these papers.

3.1 Word2Vec

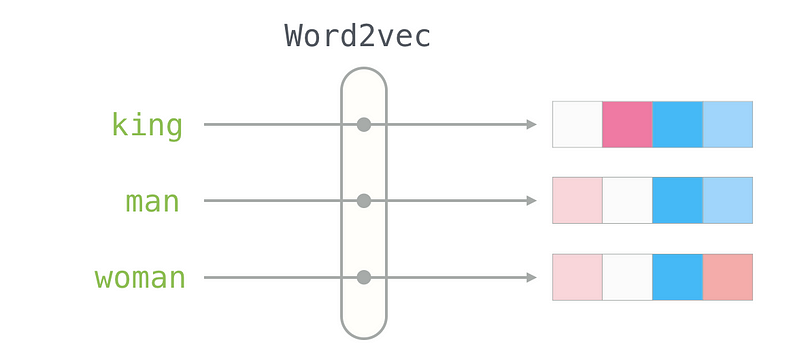

Gensim is a useful library when it comes to mapping each word into a semantic vector, which is called the embedding vector. After turning words into embeddings, words with similar meanings with have similar embeddings.

The concept of embedding

To put all the text data into the Word2vec model, we have to parse the texts into lists of strings. NLTK can help transform a bunch of long texts into short lists of tokens.

|

|

After applying preprocessing functions to all of our text fields, we can merge all fields to get a training corpus, with which Word2vec model can learn the relations between words. Here we choose the embedding size to be 256.

|

|

Then, this model can be used to generate embeddings for all words in the vocabulary. But to get an embedding for an abstract, we need to sum up all the embeddings of words in this abstract. For queries, it is the same thing. Embeddings of documents are pre-calculated while the embedding for queries are generated on-the-fly.

3.2 Preparing the features

For each pair of query and document, we join the metadata with the pairs and start extract the features which can measure the relations between the query and the documents or some characteristics about the documents.

We defined four types of features for this task:

- Similarity between the query embedding and the documentem beddings. We included three types of “distances”: inner product, cosine similarity and Euclidean distance

|

|

- Relevance score given by PyTerrier. We have adopted the methods of TF-IDF, BM25, CoordinatMatch to score the texts.

- Some basic attributes of the documents, such as the year, the conference, whether it comes from a workshop and whether it has supplementary materials.

|

|

- Whether part of the query matches the author names.

3.3 Learn-to-rank with LightGBM

The library of lightgbm is a well-written, open-source library in Python based on Scikit-Learn. So we can easily use this library to train our model with sklearn APIs. Also, this class has implemented a version for listwise ranking, which is most suited for our task of learning to rank. For training, we directly use the annotated relevance from 1 to 5 as the target label and fit the model using the features extracted and the corresponding labels.

|

|

4. Results and Discussions

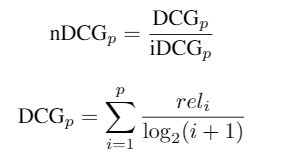

First, let’s introduce the metric used in our project. nDCG is a type of weighted sum of relevance scores of a sorted list of retrieved documents.

where relᵢ is the relevance score of the i-th document, and iDCG is the maximum possible DCG score when the order becomes the ideal order. This metric attaches more importance to the correct ranking of top-k results.

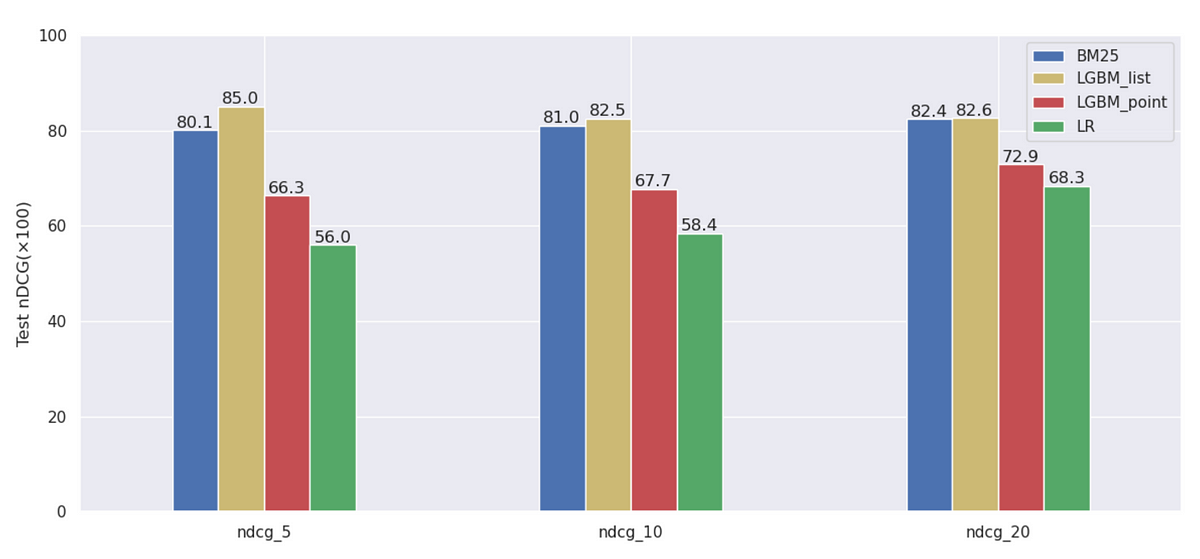

Then let’s compare our list-wise LGBM with other baselines we have mentioned above.

The list-wise LGBM outperforms other models.From the figure, we can see that listwise LGBM model works best, while pointwise LGBM and logistic regression cannot exceed BM25. The result is close to what we expect.

LGBM is a boosting algorithm, but logistic regression is a single model. Therefore, it is reasonable that aggregation of different models work better than a single model. Besides, LGBM is able to fit non-linear features, while, as a generalized linear model, logistic regression cannot fit non-linear features well.

The reason why listwise model works better than pointwise model is that listwise model can simultaneously learn both the relations between queries and documents and the relations among different documents given the same query. The essence of reranking is to re-permute the documents. Thus, the score is not the key, but the ordering is. Pointwise model focuses on predicting a score for each sample, but neglect the relation among different samples.

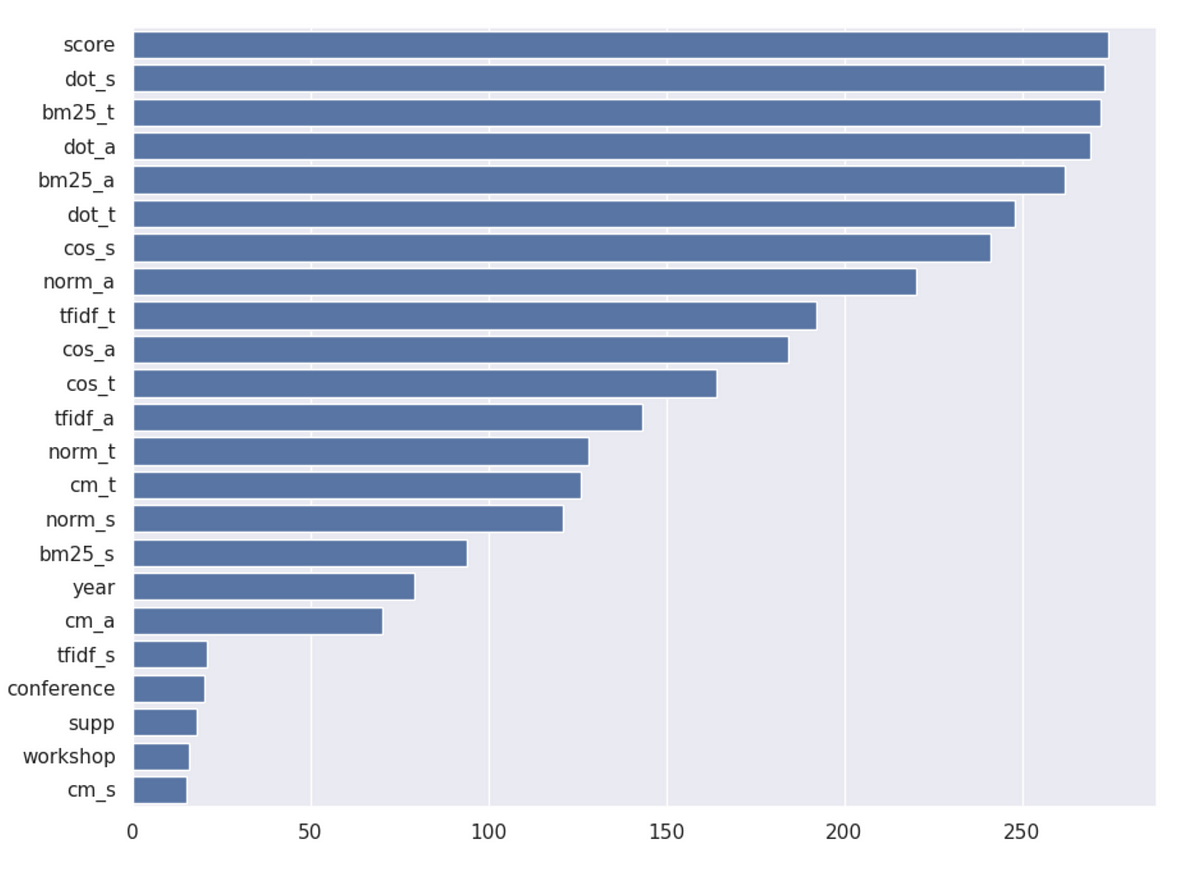

To make more sense of how our model works, we are wondering what features play important role in our model, and the tool to find that out is feature importance. Usual methods include linear regression and tree-based methods. Considering our model LightGBM is based on decision trees, we can easily acquire the importance of each feature.

|

|

The number shows how many times that the feature has been used to split a node in decision trees of LGBM. The more times it is used, the more crucial the feature becomes.

The ranking of feature importance of our LGBM model.

The ranking of feature importance in our LGBM model.In the picture, “score” is the weighted sum of BM25 scores of different parts of a document. The suffix “s” stands for subtitles, “a” for “abstract” and “t” for title. We can get that the most important features are BM25 scores and innerproducts of embeddings, which agrees with our expectation.

5. What’s Next

There are some possible improvements in our future work.

- More Powerful Models. Tree-based algorithm divides data into bins, which may lose accuracy when dealing with contiguous variables. Large language models based on deep neural networks like BERT probably work better.

- Query Design. Our queries might be subjective. We cannot design queries that are related to unfamiliar computer vision topics. An objective way is to refer to some overview papers that divide computer vision into different fields. Then, we can design queries that cover all the fields.

- Annotation. The distributions of scores labeled by two members are different, which might be a potential problem. We may need to design a rigorous rule of labeling.

- More Data Sources. We can include more computer vision conferences, such as ECCV, into our database.

- Sampling. Negative sampling is a good way of data augmentation. And it is also a good way to balance the labels if low-relevance samples are under-represented.